Three ways to add value to your offer

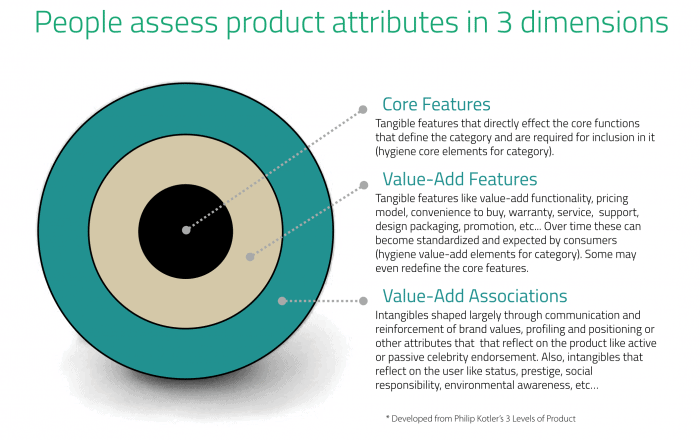

What separates the category leaders and successful disrupters from the other 99% of marketers? They see their product in 3-D just like their customers do. Look at the most exceptional marketing companies, and inevitably you’ll find them constantly adapting and developing their product’s core features, value-add features, and value-add associations to keep up with customers and well ahead of their competitors.

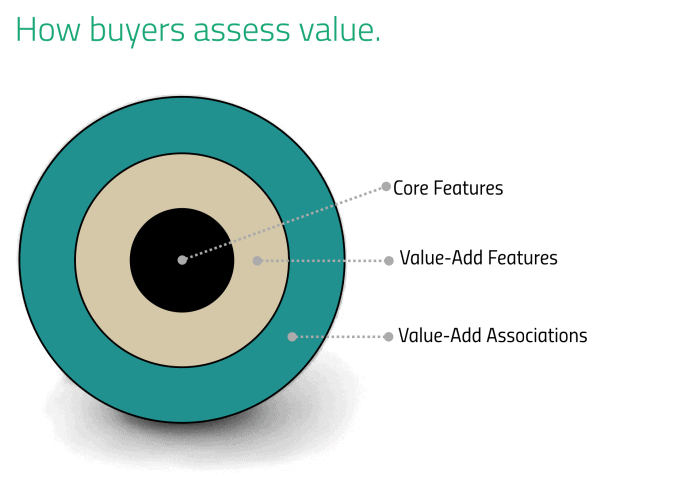

All products are 3-D - perception of value

Every time a buyer makes a purchase decision, whether a new car, a candy bar, or industrial drill bits, they are assessing their options in the same three dimensions. The exact criteria for each dimension change from product to product, situation to situation, but the underlying principle remains the same. That means this model can be used to increase and manage the value perception of any product or service, including yours.

There are usually all sorts of reasons why people choose one brand over another. Some reasons are rational, many are irrational, but all influence purchase decisions. Several years back, we tried to categorize these different factors. We began with Philip Kotler’s product model, and then we modified it. What we ended up with are three sets of attributes that prospects use when assessing a purchase.

Core features of product

These are the tangible features that define the category and are required for inclusion in it. For instance, to call a ball a Pilates ball, it has to measure 55 to 75 CM in diameter, be made of puncture resistant PVC, and be able to absorb significant shock without rupturing. Those are the minimum requirements for inclusion in the category of Pilates ball.

If the product or service category succeeds, core features will be copied by competitors over time, patents notwithstanding. The know-how required to copy core features often devolves from the status of trade secret to common knowledge as a category matures. Core features tend to be the easiest for competitors to copy.

Value-add features

These are tangible features like value-add functionality, payment terms, convenience to buy, warranty, customer service, support, design packaging, portioning, sustainability efforts, etc. When several producers offer the same core product, we can expect them to start competing on value-add features.

Like core features, value-add features can also be copied. In fact, popular value-add features can become standardized and expected by consumers (hygiene elements for category) while still not being core features. For instance, a standard value-add feature of cell phones is the inclusion of camera.

In the case of the Pilates ball, incorporating ridges along the outside of the ball has become a fairly standardized value-add feature, as has offering a variety of sizes and colors to choose from. Less common value-add features could be anti-bacterial surface coating, air pressure indicator, or even using a more environmentally-friendly material (since PVC has a large carbon footprint and is not recyclable).

How do market leaders use added value?

Value-add features are a brand’s primary canvas for innovation and differentiation. Apple and Gillette are masters at this. Category leaders typically use their position to adjust value-add features regularly and keep competitors off balance. For instance, McDonald’s took years to plan and source the children’s ball rooms it incorporated into its restaurants, achieving maximum cost-effectiveness. Once launched, Burger King had a matter of weeks to respond at great disruption and cost to their business. Value-add features may be easy to copy, but can be hard to keep up with. That’s how category leaders and disrupters tend to use them. They keep a close watch on their prospects, mining insights on a regular basis. Then, and as new trends evolve among their target segment, they are first to respond with corresponding product innovation in terms of value-add features.

Value-add associations

These are intangibles that reflect on the product, like quality and reliability, and which are shaped largely through communication. We often call this brand image. These associations can reflect on the user by providing them with perceived status or elevated prestige. The brand can be associated with celebrity, trend, social responsibility, environmental awareness, or a certain set of values.

For instance, if a popular celebrity is photographed by paparazzi using a certain brand of Pilates ball, then we could anticipate a boost in sales among fans of the celebrity who see the photo. The Pilates ball itself has been unchanged by the celebrity, yet its value to consumers has increased nonetheless by association.

Value-add associations are shaped by each brand’s unique brand strategy. The more skillful the brand management strategy, the more it will differentiate the product, generate affinity, and be difficult to copy. These aspects are the least tangible, but, in many cases, they are what sets one product apart from others in its category and forms the basis for positive (or negative) brand bias.

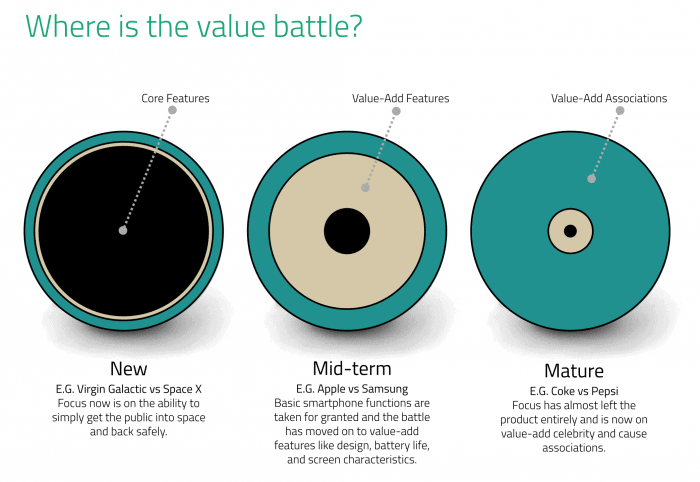

All dimensions of value are dynamic

The importance of any one of these rings changes over time as categories mature. Competition between products in a category typically begins at the core product level. As the core products become more uniform, brands will tend to compete on value-add associations. Cell phone handsets began competing on the quality of the signal in the early 1990s. When consumers no longer saw that as a problem, phones began to compete on design. Competition continues today with other value-add features, although brand associations (e.g. the coolness factor of Apple) can play a role. In very mature markets, value-add associations often increase in importance. It could be argued that, at this point, Coke and Pepsi are primarily competing on the level of brand associations.

This underscores the need to monitor a target market segment to see where the value battle really is. In the cell phone example above, Swedish handset provider Ericsson ruled the handset market at the outset with their focus on core engineering features. Nokia saw that the value battle was moving on to design, where they placed their focus and which ended up devastating Ericsson’s market share. Ericsson was fighting an engineering battle, while Nokia was fighting a design battle. The more relevant brand won. Later Apple would introduce the new category of smartphone and eclipse Nokia.